TAVR Procedure Helps More People with Aortic Stenosis

A national leader in cardiology research, the UVM Health Network is bringing the benefits of TAVR to more Vermonters and New Yorkers with aortic stenosis.

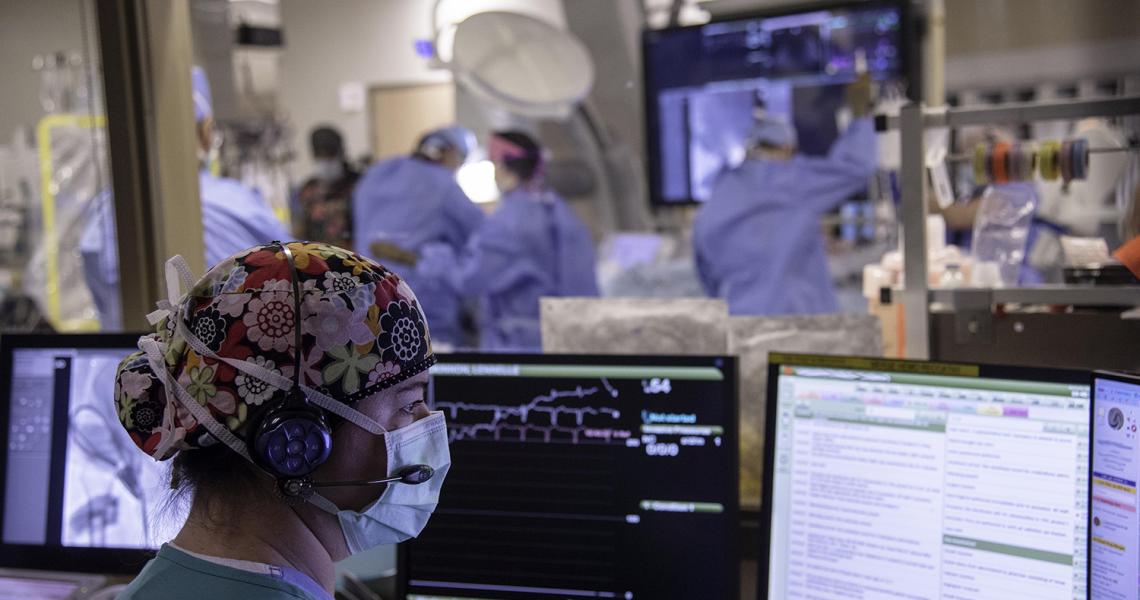

From behind the glass, Jean Laird, RN, works with her colleagues to prepare an advanced and minimally invasive technique to replace a person’s failing aortic heart valve. This is the first of the day’s three transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) procedures. Far from an observer, Laird is helping to coordinate the tightly choreographed procedure, communicating via headset with her colleagues in the procedure room as she monitors vitals and other developments from her station behind computer monitors.

Over the course of the procedure – which typically takes about two hours – a close-knit team of nurses, interventional cardiologists, nurse practitioners, anesthesiologists and cardiac surgeons will use continuous imaging and a series of catheters to insert a new artificial aortic valve. The new valve – about the size of one’s thumb – begins its journey to the heart through a small incision near the leg, where catheters are used to slowly move it into position in the heart. Miraculously, the artificial valve is put in place without the heart ever missing a beat.

“Not long ago, a patient like this wouldn’t have had many significant treatment options – frankly, they wouldn’t have much time left,” says Laird, referring to the 85-year-old man being prepped for the procedure. His condition, severe aortic stenosis, is a form of valvular heart disease that prevents the aortic valve from opening properly, forcing the heart to work harder to pump blood through the valve and to the rest of the body. This causes pressure to build up in the heart’s left ventricle and over time can lead to debilitating chest pain, dizziness and shortness of breath.

“My grandfather was in that boat, but instead, he got the TAVR procedure and got to dance with me at my wedding,” Laird says.

From a rarity to a clinical essential

Only a decade ago, TAVR was something of a rarity in the world of interventional cardiology and cardiac surgery – a procedure reserved for high-risk patients. In most cases, these were individuals that were simply too ill to undergo conventional heart valve replacement surgery, a comparatively invasive operation with longer recovery times. Recovery from TAVR typically only takes a few days.

Now the TAVR procedure has become a clinical essential for the University of Vermont Health Network, one offering even younger Vermonters and northern New Yorkers with a new lease on life. Today, cardiology experts at The University of Vermont Medical Center – known collectively as the structural heart team – perform more than 300 TAVR cases a year, the only hospital in the state and northern New York to offer the procedure. By comparison, they performed fewer than 24 TAVR procedures in 2012, the first year the procedure was offered here.

In 2022, U.S. News & World Report recognized the UVM Medical Center for its work in interventional cardiology, designating its TAVR and heart attack programs as high-performing care.

“Early on, we saw TAVR’s potential to be transformative for our most critically ill patients,” says Harry Dauerman, MD, director of interventional cardiology and structural heart interventions for the UVM Health Network. “But we also saw its potential to help a much broader collection of patients suffering from aortic stenosis. The growth we’re seeing in TAVR now is the product of 20 years of careful research, team development and investment in the advanced technologies needed to offer this high-quality care in a timely manner.”

A national leader in TAVR research

Over the past decade, the structural heart team, led by Dr. Dauerman and Frank Ittleman, MD, have been advancing national research to look at whether TAVR should be used more widely. For example, they participated in the clinical trials that cleared the way for TAVR to be used more readily with younger and lower-risk patients. They’re currently leading a new study to determine the appropriateness of TAVR amongst people with moderate aortic stenosis in the hopes they can treat more people before they develop severe disease and long-term complications. Meanwhile, they’re conducting a clinical trial that will explore the use of a TAVR-like procedure to replace mitral heart valves as well.

Cat Falduto, a nurse practitioner with UVM Medical Center interventional cardiology, says that the growing use of TAVR is making an enormous difference for people in the region with aortic stenosis.

“TAVR can add years onto a person’s life, but more importantly, it greatly improves their quality of life – making it easier for them to do life’s daily tasks,” says Falduto. “By now, I’ve worked with a lot of people who came out the other side of TAVR and within a few days were walking around feeling better than they had in years. It is such a satisfying thing to see.”